The Build Up

Global borrowing has been rising so rapidly due to recent economic events and incidents around the world, that many are worried is becoming unsustainable. According to the new OECD forecasts, as increasingly stringent containment measures required to control the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19), would inevitably lead to significant short-term if not long-term GDP decline for several major economies. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) estimates total world-wide debt (which is made of borrowing from household, companies and government) to be made up of about $253 trillion which is about 3 times the annual GDP for the entire world which was $84 trillion in 2018. The amount works out at around $32,500 for each of the 7.7 billion people on the planet. The staggering numbers don’t stop there, as it is believed that the debt per person worldwide will keep increasing accordingly $33,000, $33,500, $34,500, $35,000, $35,500 and so on at the rate of 1.5% according to the World Bank.

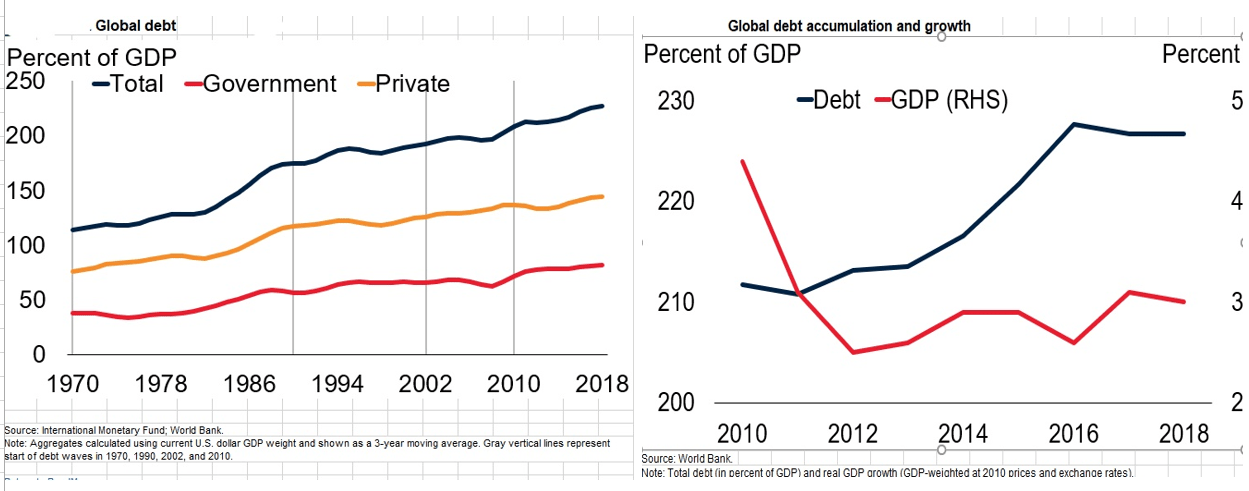

Global debt has risen to an all-time high of 230 per cent of GDP in 2018 in the new surge ongoing since 2010. Debt build-up in Emerging Markets and Developed Economies (EMDEs) was especially rapid. Total debt in these economies has risen by 54% of GDP since 2010, to a record high of about 170% of GDP in 2018. Despite a steep decline during 2000-10, debt has risen to 67% ($268 billion) of GDP in low-income countries in 2018, up from 48% (around $137 billion) of their GDP in 2010.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Shaping up Global Debt

Some are now contrasting COVID-19 to the global recession in 2020, comparable in severity to the recession of the past global debt wave of 1981-1982 & 2008-2009, so the debt rise is encouraged by the new COVID-19 pandemic virus and the financial market change that supported borrowing. Total debt across the household, government, financial and non-financial corporate sectors surged by some $9 trillion in the first three quarters of 2019 alone. In mature markets, total debt now tops $180 trillion or 383% of these countries’ combined GDP, while in emerging markets it is double what it was in 2010 at $72 trillion, driven mainly by a $20 trillion surge in corporate debt profile. Spurred by low-interest rates and loose financial conditions, the IIF estimates that total global debt will exceed $257 trillion in Q1 2020, while non-financial sector debt is now approaching $200 trillion. Global government debt alone is set to break above $70 trillion.

For the most part, the government assumes debt to boost the economy by financing capital projects, social services, etc. This is the reason why countries with developed economies are generally seen as a safe investment when borrowing because even if they spend beyond their means they can raise taxes or print more money to ensure they pay back what they owe but loans to countries in emerging economies especially sub-Saharan Africa countries are generally seen as much riskier. Ultimately, when it comes to national borrowing, it is a significant risk that a country will fall behind its debt obligation and this is not usual in default, but it happened before. Between 2010 and 2018 average public debt in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 40% to 50% of GDP, the fastest increase of any developing region (The Economist) as more than half of African countries are above the IMF’s recommended limit for public debt. The World Bank says that 29 out of 47 African countries need to tax more than they spend just to keep their debt constant as a share of the economy. But their tax revenues are about to plummet and the cost of borrowing is soaring as investors flee to safety.

The World Bank further believes the speed and scale of this debt is something the world should be worried about, so much that it urges government around the world to make it a primary concern after this current pandemic as pass away. IMF chief Georgieva said that the global economy is now in a recession thanks to COVID-19. And the international body said they “stand ready” to use its $1 trillion lending capacity to help countries around the world that are struggling with the humanitarian and economic impact of the novel coronavirus.

Calls for fiscal stimulus and increased debt are becoming the trend of the day in both developed and emerging markets, in the current climate of low growth levels and interest rates, which are projected to stay low in the foreseeable future, and monetary policy at an almost dead-end globally. It’s not just about economics indicators anymore, business and consumer behaviour change drastically. Although not a usually popular number, the amount of ammunition being dispersed to calm the economic crisis has indeed reached twelves zeros. The total stimulus package released by the US, Germany, Britain, France and Italy comes to a total of $17.4 trillion or 23% of their GDP. As it has been made valid the US has agreed on plans for a $2 trillion (10% of its GDP) recovery package to deal with the coronavirus. This includes $500 billion in loans to small businesses and another $500 million for direct cash payments of $1000 per person to American citizens for two months. The UK released €350 billion (10% of its GDP) in loans and aid for businesses. Globally, there have been at least 26 interest rate reductions, the idea being that lower rates will allow both governments and large businesses to borrow more cheaply.

Nigeria’s Debt profile Amid Coronavirus

The price of oil hit its lowest level in 18 years, declining from $66 per barrel at the beginning of the year to around $24 per barrel within which Nigeria as an oil-producing country is affected. As oil prices dropped, the Federal Government initially came out and announced a revision to the budget. It then went on to announce a cut of the N10.6 trillion budgets for the year 2020 by at least N1.5 trillion, and a change in the benchmark oil price from $57 to $30 per barrel, expectation of a potential naira Devaluation also followed. Nevertheless, the value of naira weakened, leading to a black market increase from $1= #360 to $1= N410 and in other to avoid panic the CBN put out a statement to categorically deny any plan of devaluation and then proceeded to pump more dollars int the system. The parallel exchange rate has now settled around $1= N380.

To combat the current situation, the CBN introduced six monetary policy which was essentially to ease borrowing conditions for small & medium-sized business currently under their intervention funds- Reduction in interest rates from 9% to 5% and extended the loan repayment by a year. The main beneficiaries are farmers under schemes such as the anchor borrowers’ program and other SMEs in the sectors such as textiles and Power.

The apex bank also added healthcare, and any coronavirus (COVID-19) affected businesses to the benefits of its investment fund. Finally, N50 billion in credit was announced to fund companies and partner with banks to continue lending to the real sectors. While attempts are being made by the apex bank, the FG has to come out with its chest and directly injected money into firms and households.

Budget cuts and even currency devaluations may be appropriate but may not be sufficient. The devaluation expected by foreign investors and organizations would place the country in a better position to borrow money from the IMF or the world bank for funding as countries around the world do, but perhaps for Nigeria, the country does not have the luxury of borrowing large sums at low rates without harming the economy. The last year has been spent debating on Nigeria’s debt profile if it was a debt problem or revenue crisis. The answer is both. Debt serving is more than 50% of Nigeria’s revenue, with the latest debt profile from the DMO (debt management office) stating that Nigeria public debt profile grew by 4.5% to N27.40 trillion as at December 31st 2019 from N 26.22 trillion in Q3 209. Total domestic debt hit N18.38 trillion while total external debt is N9.02 trillion.

To sum up, the World Bank states that the world is actually in the midst of the fourth wave of global debt (2010- present). So to avoid history from repeating itself, the government of various countries must prioritize debt management and accountability. Even though the fourth wave has shared many of the characteristics of the previous three global debt waves, including low-interest rates and a shifting environment, it has been tagged by the World Bank as the biggest, quickest and most wide-ranging simultaneous build-up of private and public debt Issued by households, companies, and in particular governments. It is tempting to believe that even higher debt levels are sustainable indefinitely with interest rates as low as they are today, even in emerging markets and developing economies.

Kudos to Nigeria and the CBN for responding to the current by introducing macroeconomic policies, mainly monetary policy in the fight against the current situation, but there is still room for progress, and more efficient fiscal policy needs to be in place, and support from the Federal Government and the country’s lawmakers would go a long way in reducing government expenditure. Effective management of debt will help lower borrowing rates and boost sustainability. Greater data transparency may also promote the detection and solution of the greatest risk.

Our analysis further underpins the need for urgent action to withstand the shock, and more concerted response from governments to retain a lifeline for citizens, and a private sector that will emerge in a very vulnerable state when the health crisis is past.

This writer can be contacted on twitter @Zu_josh

You can provide your comments in the space provided below. Additionally and should you need data backed research and analysis for your business or research needs, please send a mail to info@giftedanalysts.com