| by Greg Rosalsky / Planet Money: NPR |

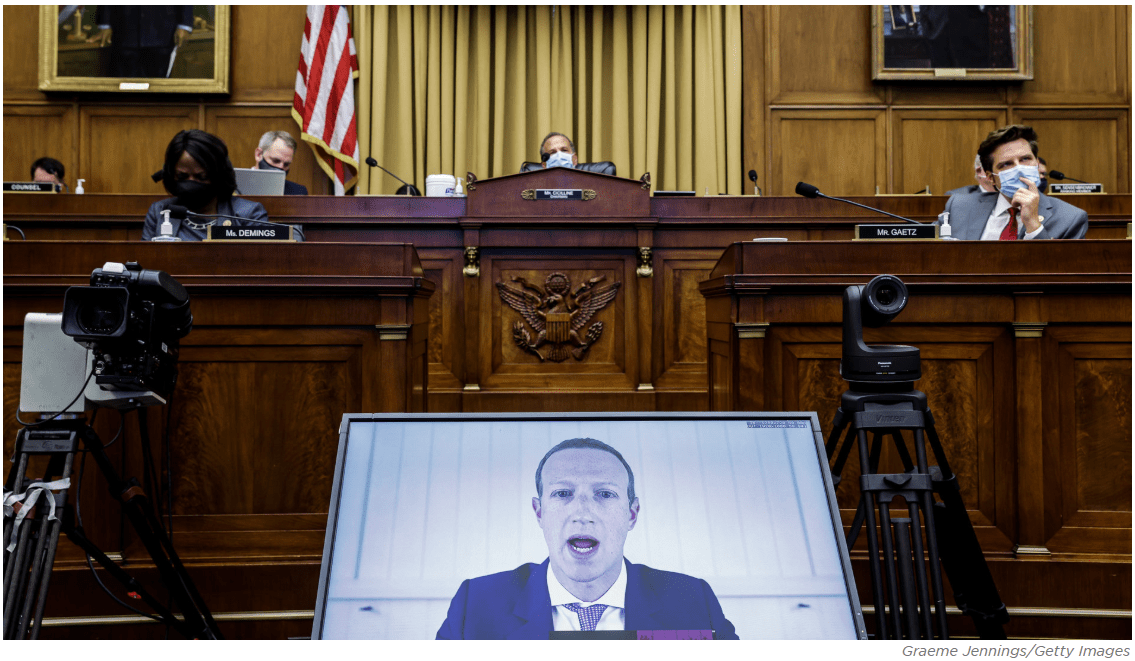

| Last week, the titans of tech Zoomed into a Congressional hearing for a flogging through their computer screens. Members of the U.S. House Subcommittee on Antitrust interrogated the CEOs of Amazon, Apple, Google, and Facebook over concerns they’re becoming monopolies and abusing their power. Both Democrats and Republicans directed much of their wrath at Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Congressional trustbusters blasted him for buying up Instagram and WhatsApp. Acquiring competitors to neutralize them is a classic move in the monopoly playbook. But the lawmakers’ gripes with the company went far beyond typical antitrust concerns. “Facebook is profiting off and amplifying disinformation that harms others because it’s profitable,” said the subcommittee chairman David Cicilline (D-RI). Cicilline and other lawmakers suggested Facebook is allowing proliferation of conspiracy theories, bogus information, and hate because it’s the type of content that keeps users engaged. “The more engagement there is, the more money you make on advertising,” Cicilline told Zuckerberg. |

|

| “I have to disagree with the assertion that you’re making that this content is somehow helpful for our business,” Zuckerberg responded. “It is not what people want to see.” He asserted that Facebook’s algorithms amplify what is “meaningful to people” and creates “long-term satisfaction, not what’s just gonna get engagement or clicks today.” Bogus information, hate, and conspiracy theories have animated American politics forever. In 1964, the historian Richard Hofstadter published an article in Harper’s Magazine, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” which dove into the storied history of crankery in the nation’s politics. In the early republic, for example, many Americans believed that a secretive Masonic Illuminati aimed to destroy religious institutions and overturn governments around the world. In the 1800s, nativist Americans widely believed in “a Catholic plot against American values.” And in the McCarthy Era, pundits claimed that even the most patriotic of Americans, like Generals George C. Marshall and Dwight D. Eisenhower, were part of a “Communist conspiracy.” Social media has supercharged the paranoid style. For example, 59 U.S. congressional candidates believe tenets in the bizarre QAnon conspiracy theory, which claims world governments are run by globalist elites who secretly participate in a Satan-worshipping pedophile ring. Bill Gates has been the target of a viral conspiracy theory that says he wants to use a COVID-19 vaccine to implant people with microchips; in April, a New York Times analysis found misinformation about him and COVID-19 was posted over 16,000 times on Facebook and liked and commented on nearly 900,000 times. Researchers at the University of Oxford recently found that 20 percent of people in England believe that Jews manufactured COVID-19 in order to destroy the economy. “Social media has allowed conspiracy theories to gain a kind of traction that heretofore just simply wasn’t possible,” says Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League, a civil rights organization that fights anti-Semitism and other forms of hate. He says Facebook, in particular, is allowing an “algorithmic amplification of some of the worst ideas.” Greenblatt worries these ideas are inspiring violence in the real world. In 2019, his organization tracked more anti-Semitic incidents than at any time in ADL’s 107-year history. This included stabbings and assaults of Jews around New York and shootings at a synagogue in Poway, California, and a kosher supermarket in Jersey City, New Jersey. In the wake of the death of George Floyd, the ADL joined with the NAACP and other civil rights organizations to boycott Facebook for allowing hate and extremism to flourish on its platform. They’re calling it the “Stop Hate for Profit” campaign. They rallied major advertisers to boycott Facebook for the month of July. “And amazingly over 1,100 advertisers joined,” Greenblatt says. “Some of the most iconic brands in the world have participated.” That includes Patagonia, Unilever, Ford, Pfizer, Reebok, Levi’s, Honda, White Castle, and Harley-Davidson. It’s true that companies are already cutting back on ad sales during the pandemic recession, and this might be a convenient time for a boycott. But Greenblatt says brands dislike having their ads associated with toxic messages and that they’re serious about getting Facebook to change their ways. He says, in comparison, other major social media platforms like Twitter—which, just before we spoke, had banned white supremacists David Duke, Richard Spencer, and Stefan Molyneux—are making “tremendous strides.” The Stop Hate For Profit Campaign has a list of ten demands for Facebook, which include taking down all Facebook groups dedicated to white supremacy, dangerous conspiracy theories, and racism and bigotry in all forms; creating “a civil rights infrastructure” to regulate content; submitting to independent audits; and reforming algorithms so they don’t amplify hate-filled or blatantly false content. Last week, The Stop Hate For Profit campaigners were joined by another campaign led by holocaust survivors, #NoDenyingIt, that takes aim at Facebook’s resistance to taking down holocaust denial-related content. When asked about the Stop Hate for Profit campaign in last week’s congressional hearing, Zuckerberg contended Facebook “is very focused on fighting against hate speech.” He said they employ 30-35 thousand people to police Facebook content, work with law enforcement and 70 external fact-checking partners, and that they’ve developed artificial intelligence that helps them “proactively identify 89% of the hate speech” before it gets seen by large numbers of people. He says they’ve “invested billions of dollars” in all of this. But Greenblatt says Facebook isn’t doing enough. And he questions Zuckerberg’s assertion that the company has a natural economic interest in banishing hate, disinformation, and conspiracy theories from its platform, insisting activists and policymakers need to continue pushing it to change. “Salacious content drives clicks,” he says. Not everyone wants Facebook’s platform more vigorously policed. At the congressional hearing, Republican lawmakers attacked Zuckerberg for censoring too much. They repeatedly expressed concern the company was using its content moderation system to stifle conservative views. “I’m concerned that people who manage the net… are ending up using this as a political screen,” said Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI). Sensenbrenner said he was concerned that Twitter and Facebook were taking down content that suggested that hydroxychloroquine could be an effective treatment against COVID-19, a claim that President Trump has repeatedly expressed support for (and which scientists have repeatedly said lacks credible evidence). Watching the live stream of the congressional hearing, it felt like both parties were working the ref of the virtual public square, and that Zuckerberg is in an awkward position where he insists he’s not an “arbiter of truth” while also feeling huge pressure to be an arbiter of truth. With the initial month-long boycott now over, Greenblatt says Facebook has failed to meet their campaign’s demands, but they’re not giving up the fight. For the time being, you’ll likely continue seeing your friends and family members spreading bogus information and crazy conspiracy theories alongside the never-ending deluge of baby and engagement photos in your Facebook feed. |

CREDIT: The Post Are Conspiracy Theories Good for Facebook? first appeared in NPR on 4th August, 2020