By Catalina Margulis and Arthur Rossi / IMF

Countries are moving fast toward creating digital currencies. Or, so we hear from various surveys showing an increasing number of central banks making substantial progress towards having an official digital currency.

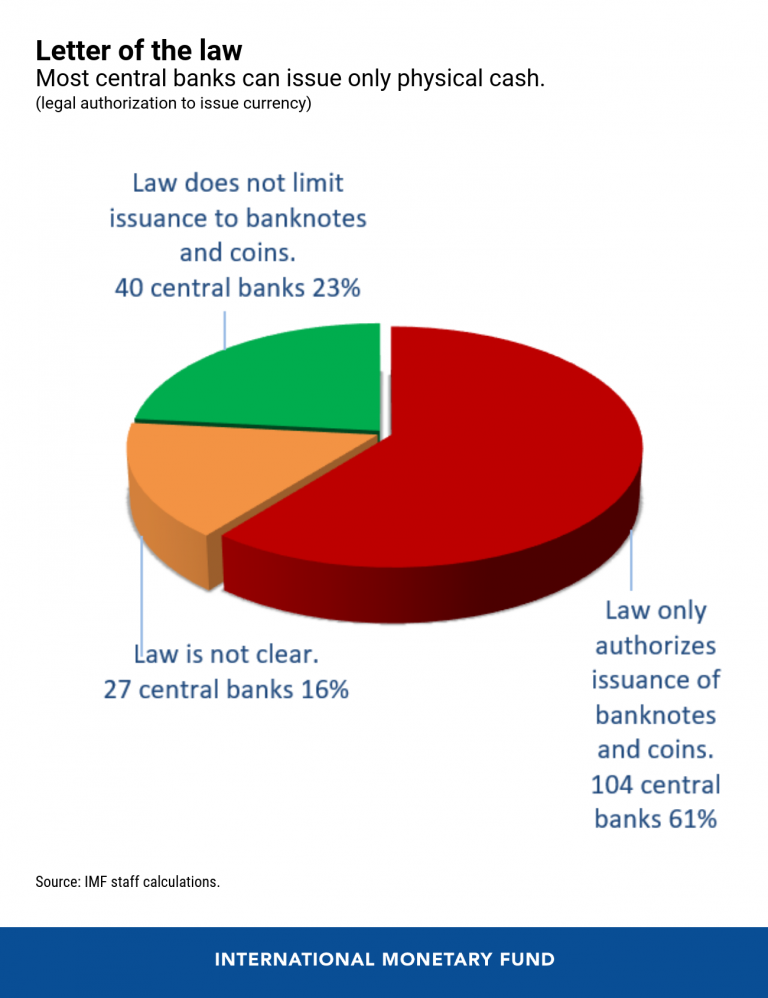

But, in fact, close to 80 percent of the world’s central banks are either not allowed to issue a digital currency under their existing laws, or the legal framework is not clear.

To help countries make this assessment, we reviewed the central bank laws of 174 IMF members in a new IMF staff paper, and found out that only about 40 are legally allowed to issue digital currencies.

Not just a legal technicality

Any money issuance is a form of debt for the central bank, so it must have a solid basis to avoid legal, financial and reputational risks for the institutions. Ultimately, it is about ensuring that a significant and potentially contentious innovation is in line with a central bank’s mandate. Otherwise, the door is opened to potential political and legal challenges.

Now, readers may be asking themselves: if issuing money is the most basic function for any central bank, why then is a digital form of money so different? The answer requires a detailed analysis of the functions and powers of each central bank, as well as the implications of different designs of digital instruments.

Building a case for digital currencies

To legally qualify as currency, a means of payment must be considered as such by the country’s laws and be denominated in its official monetary unit. A currency typically enjoys legal tender status, meaning debtors can pay their obligations by transferring it to creditors.

Therefore, legal tender status is usually only given to means of payment that can be easily received and used by the majority of the population. That is why banknotes and coins are the most common form of currency.

To use digital currencies, digital infrastructure—laptops, smartphones, connectivity—must first be in place. But governments cannot impose on their citizens to have it, so granting legal tender status to a central bank digital instrument might be challenging. Without the legal tender designation, achieving full currency status could be equally challenging. Still, many means of payments widely used in advanced economies are neither legal tender nor currency (e.g. commercial book money).

Uncharted waters?

Digital currencies can take different forms. Our analysis focuses on the legal implications of the main concepts being considered by various central banks. For instance, where it would be “account-based” or “token-based”. The first means digitalizing the balances currently held on accounts in a central banks’ books; while the second refers to designing a new digital token not connected to the existing accounts that commercial banks hold with a central bank.

From a legal perspective, the difference is between centuries-old traditions and uncharted waters. The first model is as old as central banking itself, having been developed in the early 17th century by the Exchange Bank of Amsterdam, considered the precursor of modern central banks. Its legal status under public and private law in most countries is well developed and understood. Digital tokens, in contrast, have a very short history and unclear legal status. Some central banks are allowed to issue any type of currency (which could include digital forms), while most (61 percent) are limited to only banknotes and coins.

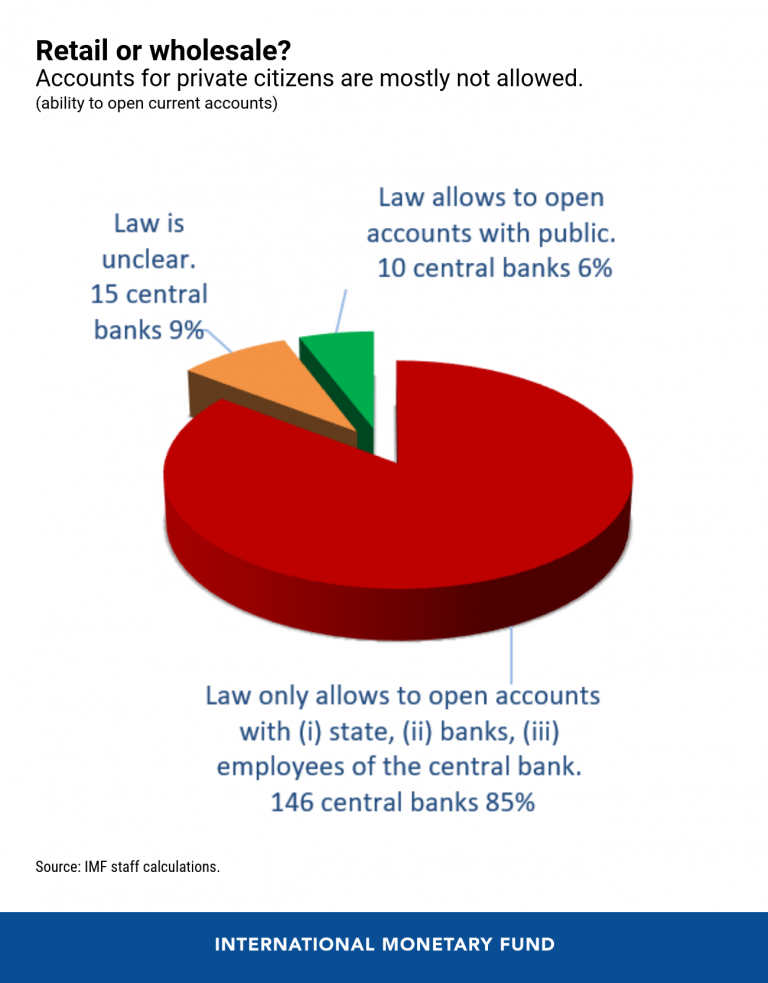

Another important design feature is whether the digital currency is to be used only at the “wholesale” level, by financial institutions, or could be accessible to the general public (“retail”). Commercial banks hold accounts with their central bank, being therefore their traditional “clients.” Allowing private citizens’ accounts, as in retail banking, would be a tectonic shift to how central banks are organized and would require significant legal changes. Only 10 central banks in our sample would currently be allowed to do so.

A challenging endeavor

The overlapping of these and other design features can create very complex legal challenges—and could well influence the decisions made by each monetary authority.

The creation of central bank digital currencies will also raise legal issues in many other areas, including tax, property, contracts, and insolvency laws; payments systems; privacy and data protection; most fundamentally, preventing money laundering and terrorism financing. If they are to be “ the next milestone in the evolution of money,” central bank digital currencies need robust legal foundations that ensure smooth integration to the financial system, credibility and broad acceptance by countries’ citizens and economic agents.

Catalina Margulis is a Consulting Counsel in the IMF Legal Department’s Financial and Fiscal Law unit, seconded from the Central Bank of Chile.

Arthur Rossi is a Research Officer in the IMF Legal Department’s Financial and Fiscal Law unit.

CREDIT: The Post Legally Speaking, Is Digital Money Really Money? first appeared in the IMF Blog on 14th January, 2021.