The Unholy Union Between the Naira and Devaluation

In 2020, the Naira lost 25% and 27% of its value at the NAFEX and parallel exchanges, respectively. This quickly disrupted my plans, as I had planned to upskill and purchase some courses priced in dollars at the onset of the year. My disappointment prompted me to visit the CBN’s website in search of its policy stance per the Naira. The website says the apex bank’s exchange rate policy is managed floating – a market-friendly term adopted by developing countries who operate some form of pegged regime. I murmured, why did the Naira not appreciate, and why is it always under severe downward pressure?

First, let’s Upskill

There are three types of exchange-rate arrangements in developing countries: flexible, pegged, and band regimes. In a relaxed regime, the currency is allowed to fluctuate in response to demand and supply changes. If the central bank does not intervene, it is called a free-float; otherwise, it is called a managed float. Band regimes exist when a central bank announced a band intended to allow the exchange rate to fluctuate within. A pegged regime has three forms: currency board where a country’s base money is fully backed by its official foreign reserve, thus, ensuring the value of the currency is irrevocably fixed; adjustable pegs in which the domestic currency is strictly fixed against a single or multiple currencies and is seldom changed; crawling pegs in which the currency is initially fixed but subsequently adjusted by the apex bank to reflect changes in inflation or trade balance.

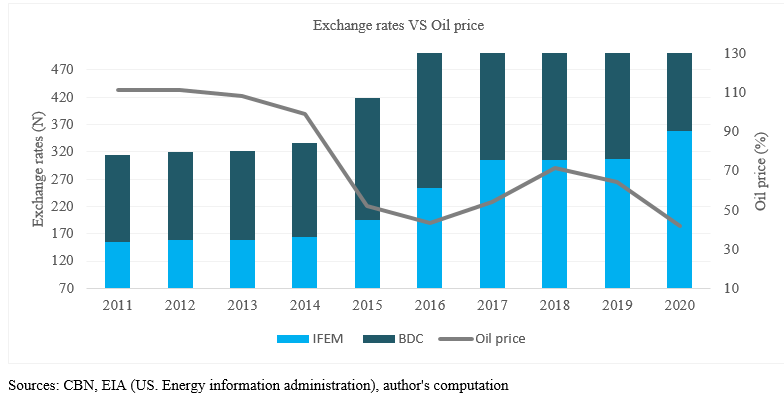

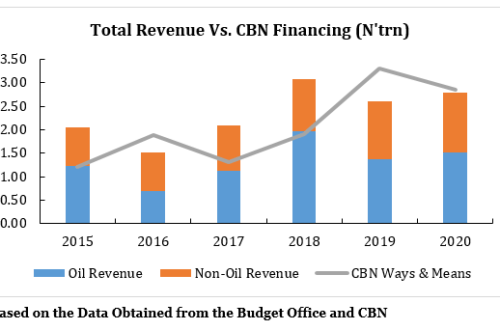

The preceding suggests that the Naira fits in a pegged regime, perhaps most fitting in the crawling peg regime, since violent exchange rate movements have followed oil price in the last ten years.

Is the Choice of Exchange Rate the Problem of Nigeria’s FX and Economic Crisis?

Considering the numerous economic insights of many policy analysts, the initial answer would be yes. Many economists have suggested that the CBN should float the exchange rate, which would allow the market to determine the fair value of the Naira. They back their position with the accompanying benefits of floating exchange rate, which include: it will enable the central bank the flexibility to influence the money supply and other economic variables without unnecessarily worrying about their impact on the exchange rate, it makes export more profitable and will boost domestic production and employment, and lastly, it makes a country resilient to external shocks – perhaps an external shock like the coronavirus that led to oil price crash in 2020.

For the last point, the argument is that the government can devalue its currency below the growing inflation rate—which is partly caused by devaluation–such that employers of labour find it profitable to continue production and exportation without retrenching workers. With this line of thinking, it is clear that devaluation proponents understand the critical impact of devaluation on the inflation rate.

However, stemming from the above, there must be three preexisting conditions for a country to benefit from devaluation. First, the economy must be diversified to wither external shocks. Think of it this way, if the Yen depreciates by, say, 15%, importers of Tesla in China will find it more expensive to import Tesla into the USA. This, in turn, should have an income effect on lovers of Tesla, such that the demand for Tesla in China will drop. However, we are unlikely to see that scenario play out because there are other luxurious cars that lovers of Tesla can switch to whenever Tesla becomes excessively expensive. Likewise, if Panasonic TV becomes excessively expensive in South Korea because of the weakening Korean won, Koreans can easily switch to a locally produced Samsung TV. My point is, there is a limited inflation pass-through effect on production in a well-diversified economy since there are alternative inputs for production and finished goods locally. Hence, weakening local currency’s substitution effect will outweigh its income effect.

Similarly, for a sustainable floating exchange rate system to work, a country must have diverse foreign earnings. This is alien in Nigeria, as oil revenue contributes about 90% of total foreign earning. Worst still, the product’s price and volume are not determined by the country; instead, OPEC+ fixes them (output in this case, with an indirect impact on price) depending on market dynamics. Hence, Nigeria cannot increase revenue from oil at will to meet its development goals.

Another preexisting condition for a successful floating exchange rate system is that such currency holders must feel comfortable in their currency’s standard of the value function. This is a rare phenomenon in a monoculture economy like Nigeria, where the country has a foreign reserve susceptible to external shock because the export base is shallow. To compound this, it has a central bank with diminished credibility. A central bank loses credibility in the exchange rate whenever it says it won’t devalue and it goes ahead to devalue.

At this point, you may have noticed that I have used devaluation and floatation of exchange rates interchangeably. It is deliberate; as in Nigeria, floatation is often confused to mean devaluation (maybe rightly so). At the same time, it means an upward and downward, possibly gentle exchange rate movement. One can, however, forgive this mistake since every attempt to float the Naira has often meant the currency has to be significantly devalued.

That said, looking at these three preconditions, devaluation (or floatation as it is often confused with) itself will not provide succour, nor will it provide a sustainable solution to Nigeria’s exchange rate crisis.

Is a Pegged Exchange Rate Regime the Necessary Succor and Sustainable Solution to the FX Crisis?

I believe it won’t shock you if I answer No. Well, the answer is No.

The CBN has a valid point for continuing to defend the Naira and limiting excessive volatility in the FX market. Inflation has continued to surge since 2019, printing 16.47% y/y in January this year – the highest in over three years. Aside from policy mishaps like the border closure and security challenges, another chief contributor to the surging inflation figure is devaluation. Nigeria’s manufacturing sector and even the services sector like agriculture rely on imported raw and intermediate production inputs. Hence it is not difficult to see how devaluation will impose an upward trajectory on the already alarming inflation rate.

However, the CBN has erred in its approach to handling the FX management. Weak fundamentals of the economy coupled with a fragile, if not lost, credibility of the apex bank have rendered the fight for maintaining the Naira’s value a lost one. Sustained attempt to defend the Naira amidst the market attempt to correct its valuation to its fair value will further attract the currency’s speculative holders. The CBN governor, Godwin Emefiele, alluded to this speculation attack on the Naira when he said after the November MPC meeting that the wide gap between the NAFEX and parallel exchanges does not reflect the fundamental value of the currency.

To understand the consequence of a central bank’s diminished credibility under a pegged regime, consider this chain of events: an economy that operates a pegged regime would typically have an exchange rate crisis when it has created a divergence between inflation and the value of its currency over time. It does this in either of two ways: (i) it continues to print money above the economy’s productive capacity or above the level which its financial sector is willing to deploy. This, in turn, results in inflation and an increasing current account deficit in the balance of payment. (ii) An undiversified economy that has high a penchant for imports will also see inflation shoot up at the instance of devaluation. Its current account balance will also report a deficit in the balance of payment in the event of a sustained external shock.

The local currency loses value once the central bank overzealously and persistently hit the money printing press beyond the level the economy requires (or whatever factor drives up inflation). To maintain the local currency’s value, the central bank intervenes by selling dollars in the market. As their dollar reserve gets depleted (or it is unwilling to deplete it because of the volatile nature of its foreign earnings – think of oil), they call on the IMF for more dollars. The IMF then gives its conditions (often referred to as conditionalities) before availing them with dollars. Because the currency would be overvalued over time due to sustained defense by the apex bank (Inflation would have outstripped devaluation over time), one of the IMF conditionalities usually involves devaluation of the currency’s fair value hitherto the defence by the apex bank. The government will go back and forth until they eventually succumb to IMF demands and devalue their money—sometimes violently.

The chain of events described above mirrors the events that preceded the 1986 structural adjusted program in Nigeria recommended by IMF on the back of the crash of oil price. This same chain of events is playing out now in Angola, a monoculture economy that also relies on oil for about 90% of its foreign earnings. Its currency, the kwanza, has since lost more than 220% of its value since 2017 in a bid to reprice to its fair value on the back of limited foreign earning since the 2015 oil price crash. The country is implementing an IMF structural program.

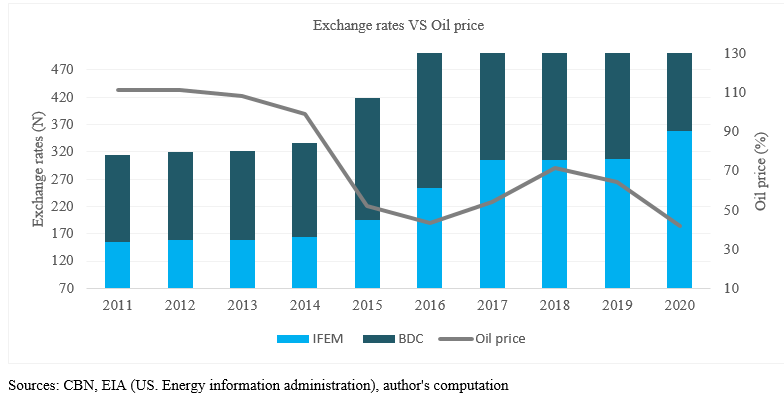

Aside from the policy mishaps identified earlier, which have driven inflation, the CBN quasi-fiscal interventions like NISRAL is compounded by the CBN’s overzealous and persistent hitting of the money printing press through its ways and means program to support the fiscal deficit of the federal government – which continues to put downward pressure on the Naira. The pronity to speculate the pegged regime and weak fundamentals like undiversified export earnings make the current FX management of the CBN very costly and would not provide a sustainable solution to the lingering Naira crisis. Its fervent focus on the exchange rate and continued reliance on foreign portfolio investments through high interest could be impacting long-term investments by the private sector through the high cost of finance.

Recommended Reading: A Beginner’s Guide to CBN’s Ways and Means to the Federal Government of Nigeria

What, then, is the Appropriate FX Policy Approach?

Again, again and again, the market has insistently shown that knee-jerk and short-term exchange rate policies like import control, capital control, hot money flows or even the recently introduced daily dollar spending limit will not prevent the Naira from violent devaluation. Thus, the country’s exchange rate debacle should be looked at from a minimax policy decision approach; that is, which policy option has the least adverse effect on the economy considering its existing structure and the described advantages and disadvantages of the various regimes. The economy is certainly better-off with a floating exchange rate system if this is done.

Whilst a stable exchange rate, which is the aim of the CBN, will help stabilise price and the economy, the fundamentals of the economy and the loss of credibility of the apex bank has made this aim challenging to achieve. In the short term, the CBN should stop its capital control measures, which would attract foreign portfolios and direct investments. Similarly, on the part of the fiscal authorities, government policies should be clear both at the national and state level. Investment bottlenecks like a weak property right and the rule of law need to be strengthened. In the same guise, structural improvement in electricity pricing should be consolidated by essential infrastructure development in the transport sector. The cumulative impact of these solutions will ensure that long-term capital can flow into the economy, which would expand the production base. By extension, export earnings needed to provide a fighting fist for the Naira and its store of value function can be restored.

4 Comments

Hae

Nice article.

It’s Korean won though not yen.

Abdulazeez Kuranga

Thanks for the correction Hae. It has been effected.

Terhemen Agabo

A great and insightful article. The floating exchange rate system as you noted can only withstand shocks in a diversified economy . But diversification will take over a decade even if the government begins full implementation today. What exchange policy then can be adopted in the short term pending when the economy is fully export diversified?

Abdulazeez Kuranga

I think the short term solution will be to devalue the currency to its fair value (around 450/USD according to some estimates) so as to attract more dollar inflows, improve liquidity in the FX market, clear backlogs and constantly communicate FX guidelines to the public. The communication is very important in letting investors know what the CBN expects to happen in the future as well as increases the credibility of the CBN so far it stops going against what it says it will do and not do. With all the aforementioned in place, then the current regime of managed float should work pending the full export diversification.