By Greg Rosalsky / Planet Money

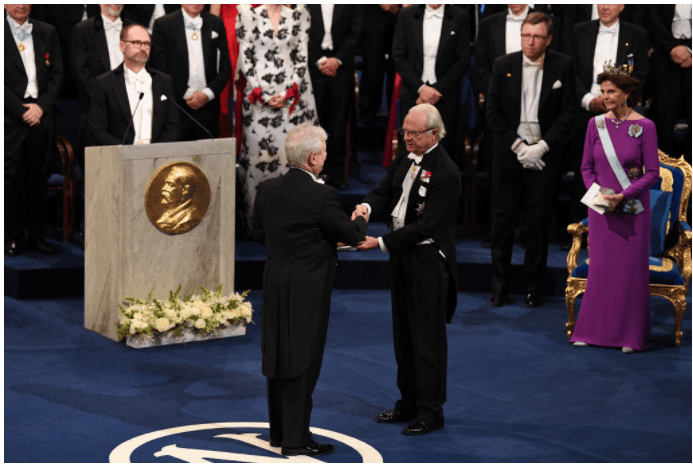

| Sure, the book Nudge may have become a cultural phenomenon that ended up selling millions of copies. And, okay, it resulted in hundreds of governments and countless companies around the world adopting its concepts and methods. And, yeah, its co-author Richard Thaler went on to win the Nobel Prize and appear in an Oscar-winning movie starring Brad Pitt, Christian Bale, and Ryan Gosling. But, Thaler says, when they were trying to sell the book back in the mid-2000s, he and co-author Cass Sunstein had a hard time finding someone to publish it. “Basically, all publishers rejected it,” Thaler says. “So it was originally published by an academic press.” It was only when the book was set to become a paperback that a commercial publisher saw its potential and bought the rights. Maybe it took off because the 2008 financial crisis sent society searching for alternative economic ideas. Or maybe it took off because the book had a catchy title and good artwork. Whatever the reason, Nudge caught fire and finally brought behavioral economics into the mainstream. |

| Thaler is a professor at University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and one of the founding fathers of behavioral economics. Before Nudge was published, he had spent years mostly in the Ivory Tower, scolding fellow economists for dogmatically clinging to an unrealistic portrayal of human behavior. The dominant model in economics was a cartoon that painted humans as supernaturally rational creatures, with the power to always make optimal decisions with laser-like focus and discipline. These creatures were free of cognitive flaws and emotions. They had perfect self-control and clarity of judgement. And while they did face constraints like a fixed budget or limited information, they were always able to make choices that did them the most good. Thaler insisted the dominant economic model was a poor representation of reality and that wholeheartedly embracing this model had ugly consequences for people and markets. Nudge became his manifesto. He and Sunstein not only offered evidence and theories for why people often fail to make good decisions, they offered small, practical solutions — “nudges” — to help people make better decisions. For example, they began the book with the modest example of a school administrator rearranging the display of food at the cafeteria, increasing the likelihood that kids choose a healthier lunch. A decade-plus later, Thaler and Sunstein are publishing Nudge: The Final Edition. Thaler says they put a lot of work into the revision, and their “final edition” subtitle is their way of nudging themselves into never having to revise the book again. It’s kind of a perfect, meta-proclamation of their own limitations as human beings and the creative ways we can push ourselves to achieve our goals. This version of the book is chock-full of new ideas. My favorite is probably the concept of “sludge.” One way to nudge people to do something is to make it easy to do. Sludge is like its sinister opposite: when institutions try to prevent people from doing something by making it hard to do. Think limiting the number of polling stations and causing big lines as a way to discourage voting. Sure, you can still vote, but good luck actually doing it. Thaler was inspired to develop the idea of sludge when his memoir, Misbehaving, was released a few years ago. His editor told him that the first review was published in a London newspaper, and Thaler wanted to read it. But the article was behind a paywall. To get past the paywall, there was a promotion. It cost one British pound to sign up for a one-month trial subscription. Then he started digging deeper and learned that to cancel his subscription, he’d have to give two weeks notice. And in order to do that, he’d have to actually call the newspaper’s headquarters — during London business hours! This is a company using sludge to make it harder for people to cancel their subscriptions. Another egregious example of sludge: the U.S. tax system. It’s incredibly time intensive and unnecessarily complicated to file taxes. In Sweden, Thaler says, most taxpayers can file their taxes in a few minutes with the simple push of a button on their smartphone. Thaler’s colleague, Austan Goolsbee, has proposed we allow the IRS to pre-populate people’s tax forms and make our tax experience easy, like it is for the Swedes. Congress has considered adopting such a proposal. But tax preparation companies love sludge. It creates a lucrative business where people need tax help. And they’ve spent years lobbying the government to prevent reforms that would make tax preparation simple and free. Ideas like Goolsbee’s haven’t only been shot down, they’ve been forbidden. “The IRS is not allowed to send you a completed tax return,” Thaler says. “So that’s one example of sludge that I hope this version of the book can help get rid of.” In addition to new things in the new version of the book, there are old things from the original version that are gone. That includes the research of the former Cornell professor Brian Wansink, a behavioral scientist who got caught producing shoddy research that fudged numbers and misled the public about his empirical findings. Wansink’s work is one of the more dramatic examples of a broader “replication crisis” that has plagued psychology in recent years. Researchers have been re-doing studies published in some prominent psychology journals, and, in many instances, they’ve found that their findings couldn’t be replicated. Thaler is cheering on the social scientists probing academic literature to suss out what can be proven and what can’t. “That’s healthy science,” he says. Part of Thaler’s whole mission with behavioral economics is to make economics overall a healthier science with an evidence-based view of human behavior. While there is a reckoning happening in psychology, he says, behavioral economics rests on an empirical foundation that has proven to be replicated again and again. “The basics of behavioral economics are really sound because they’re kind of obvious,” Thaler says. It’s obvious, he says, that people aren’t perfectly rational. It’s obvious that they suffer from self-control problems and have all kinds of emotions and biases that affect their behavior. The oddities of human behavior are very real and demonstrable — and economists and policymakers, he says, need to take that into account. That said, there are now hundreds and hundreds of public and private institutions nudging people around the world. Will every nudge shown to have an effect in a particular setting be replicated again and again? No, Thaler says. And we shouldn’t expect this. Behavioral economists will continue to work to figure out what works and what doesn’t. Some nudges prove to be more successful than others, like nudges that push people to institutionalize some change or stick with a default option that’s good for them. Of all the nudges that have reshaped our world, Thaler says their most significant contribution is probably pushing governments and companies to recognize the power of defaults and automatically enroll newly hired employees in retirement saving plans, rather than asking them to opt in. For a long time, new hires were confronted with a daunting set of options for 401k and other retirement plans. And humans (being humans) suffered from problems with delayed gratification and cognitive overload with too many choices. They failed to voluntarily select savings rates and investment plans that would leave them with a solid nest egg for retirement. Thaler, equipped with the insight that people tend to stick with the default option given to them, pushed organizations to automatically enroll people in sensible retirement plans. Research from Vanguard finds that participation rates in retirement plans more than triple when companies automatically enroll new hires — with 91% of new hires participating in a retirement plan when they’re automatically signed up, versus only 28% participating when they have to put in the effort to sign up themselves. If people were super rational, such a nudge wouldn’t be necessary — but these huge effects prove why behavioral economics is so important. Behavioral Economics vs The Pandemic Since the pandemic began, governments and companies around the world have had to think creatively about how to nudge people to wear masks, socially distance, and get vaccinated. And we’ve seen a lot of creative campaigns that adopt strategies outlined in Nudge. An example is appealing to people’s identities when promoting a desired behavior. I saw a great example of this last year when I was in a small town in Wyoming, “The Cowboy State.” I went into a Subway to get a sandwich, and I saw an image of a Cowboy with a mask that made him look like a badass bandit. “Mask Up Wyoming,” the sign said. |

|

| Another idea found in Nudge is to use lotteries to encourage people to do stuff. People, despite the extreme odds against winning anything, love them. And we’ve seen a number of states using vaccination as the entry ticket to potentially win lotteries. Governors in those states have been declaring the strategy to be a resounding success. Thaler says he thinks many governments and companies have done a good job of using nudge strategies to get people vaccinated. But over 40% of Americans remain unjabbed. The idea behind a nudge is to encourage people to do something without forcing or coercing or penalizing them. And while Thaler thinks we haven’t exhausted the nudge playbook yet, he thinks we may have to start — figuratively speaking — shoving people to get to herd immunity. CREDIT: The Post The Behavioral Economics Manifesto Gets Revised first appeared in www.npr.org on 27th July 2021. |