The below is a possible aftermath effect of subsidy removal, a possibility that is less discussed.

In 2021 when the Buhari-led federal government finally summoned the courage to damn the agitations of the labour union by removing fuel subsidy and embarked on long-standing fuel pricing reforms, many felt, at least many economists and analysts felt, the positive impact of subsidy removal would outweigh its adverse trickle-down effects. It is evident that the otherwise has occurred. Inflation has continued to surge unabated; unemployment has maintained its upward pattern, whilst Nigerians continue to groan at their falling standard of living.

Dangote refinery has started production, but the price of petroleum has dropped only mildly, as the company gets crude oil and sells its fuel at the international price. The federal government has little ability to dictate its price since the refinery is located in the export processing zone. However, Foreign exchange demand has reduced significantly, but Nigerians continue to find fuel price unbearably expensive and volatile. It looks as though nothing has changed, as they continue to pressure the government to revert to subsidy payment; or improve their livelihood in whatever way the government can.

The Ayes have it!

At the moment, there seems to be a consensus among intellectuals and institutional bodies like the IMF and the World Bank on the potential positive impact of the removal of subsidy on the economy. Their arguments are pretty broad and far-reaching. They submit that subsidy payment continues to widen the inequality gap in the country since petroleum subsidy is an implicit subsidy (financing consumption), and the wealthy who consume more than the poor citizens whom the government seeks to protect from the high fuel price also benefit from the regulated price. At the same time, their taxes have not increased commensurately.

In fact, the immediate past minister of petroleum, Ibe Kachikwu, exposed the smuggling activities of some senior government officials and marketers who divert subsidised fuel to neighbouring countries like Chad, Cameroon, Togo and Benin, laying credence to the IMF’s position of a disproportionate benefit of subsidy among the poor and the wealthy.

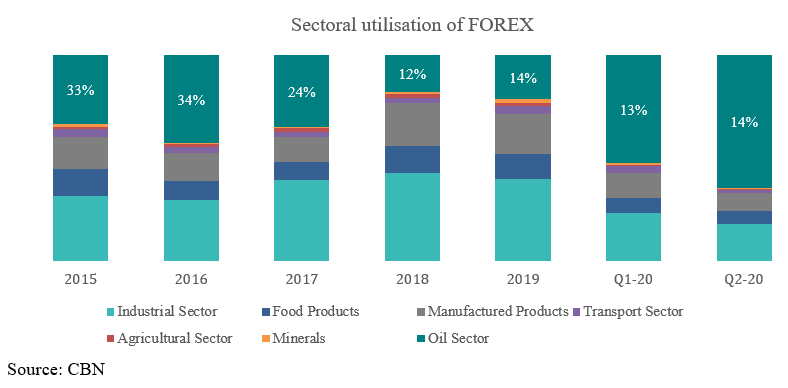

Another argument to support subsidy removal is the big elephant in Nigeria – foreign exchange. It is suggested that if the government removes subsidy and channel the amount saved to building refineries, the dollar demand for the purchase of imported fuel will reduce, thereby protecting the value of Naira. The logic is simple. Dollar demand for importation of refined oil and its derivatives account for 20% of total foreign exchange in Nigeria in the last four years; these savings would definitely give the Naira and the CBN a breathing space.

In the same guise, the IMF continues to warn on the need for Nigeria to diversify its export earnings to mitigate the impact of the volatility in oil price on the economy. Since the government covers the difference between the market and the subsidised price of oil, it is no coincidence that whenever there is a global uptrend in the price of crude oil, the need to remove subsidy payments gains momentum. Oil accounts for 88% of Nigeria’s total foreign earnings.

In March 2021, the Group Managing Director (GMD) of NNPC, Mele Kyari, revealed that the market price of fuel ranges between N211 – N234 /litre, and the government pays about N100bn-N120bn as a monthly subsidy payment covering the difference between this price and the prevailing pump price of N175/litre. Extrapolating the monthly subsidy payment to a yearly payment, assuming that the global price of crude oil will average $68/pbd in 2021, revealed a staggering amount of between N1trn and N1.2trn. This is even more disturbing when you compare the subsidy payment with the amount the government plans to spend on developing human capital in the form of expenditure on health and education. In the 2021 budget, the government implements an N742.5bn and N547.2bn expenditure on health and education, respectively.

In an MSME survey carried out by PWC in 2020, the availability and cost of electricity remain the major impediments to small business growth in Nigeria. Channelling the saving from the removal of subsidy to this sector and other challenging sectors would better serve the government to increase the welfare of its citizens.

Besides, allowing the pump price of fuel to reflect price will prevent excessive consumption by Nigerians. In 2018, NNPC estimated that Nigerians consume 54 million litres of fuel daily. While the smuggling activities of subsidised fuel fade the veracity of this data by some marketers into more profitable countries like Benin and Cameroon, a full cost-reflective pump price of fuel will inevitably reduce the aggregate consumption of fuel in the country.

Inevitably, the subsidy payment has to be stopped now when one considers the country’s projected population, which is put at 400 million by 2050. A bet on electric vehicles to reduce total consumption would be a long bet.

Addressing the concerns of the Nays

While many economists and analysts have identified the short-term impact of halting subsidy payment on the economy in the form increase in transportation cost and consequently a significant upward pressure on the inflation rate, which was reported at an alarming rate of 18.17% in March, more emphasis has been laid on the long-term positive impact of stopping subsidy payment on the economy.

A less discussed factor that this long-term hope is hinged on is the government’s credibility. It is believed that the government will channel the saving from subsidy on the welfare of the citizens and that the government will have more room to borrow and spend on capital projects that have a far-reaching positive impact on the citizens.

Considering the government’s goodwill and precedence, these expectations may turn out to be a hoax.

In 2020, according to Transparency International, Nigeria ranked 149 out of 179 countries on the transparency index. She was surrounded by countries like Cameroon, Tajikistan and Madagascar. This begs a valid question: if there is largescale mismanagement of resources by the government, why will savings from subsidy be any different?

Answering this question reveals that an outright removal of subsidy is putting the cart before the horse. The country has not put in place strong institutions to ensure resources are well-managed and that citizens benefit from rechannelling the subsidy savings to other sectors.

However, considering the constraints on the budget and the government’s revenue, there is no time to put the cart behind the horse. The country will need to put in place stronger institutions that can hold the government accountable for the resources under its management whilst effecting painful but necessary reforms.

In sum, while subsidy removal is the right policy choice, economic prosperity on the back of its removal is not a given. Economic prosperity is uncertain considering precedence on resource management in the country. More effort should be channelled to how the savings from subsidy removal is expended; if not, the Nays will have the day.