By Era Dabla-Norris, Ruud De Mooij, Andrew Hodge, and Dinar Prihardini / IMF

New global reforms will change where tech giants pay taxes in Asia and make the international tax system more robust.

Digitalization—the technology that powers fintech, e-commerce, and online services—enables us to make mobile money transfers, purchase goods and services online, and interact with people across the globe. It has created some of the largest global businesses, such as online platforms and marketplaces connecting producers and consumers across the world.

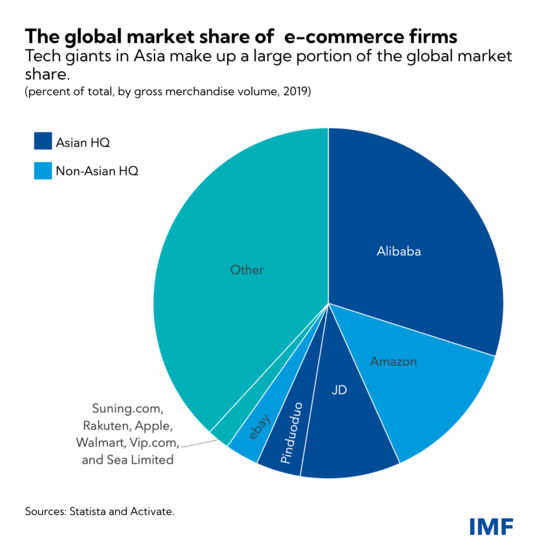

Asia alone has roughly two billion internet users, with considerable room to grow. Asia’s advanced and emerging market economies have several locally headquartered tech giants—including Alibaba, JD.com, Tencent, Rakuten—and host foreign tech giants such as Facebook. A new set of agreed global tax reforms will change where these tech giants and other global giants pay taxes.

Thus far, it’s been challenging for many Asian countries to tax tech giants especially because many are not physically but rather only digitally present in a country. Existing international norms for taxing profits, which many people consider to be outdated and unfair, haven’t kept up. Collecting taxes on cross-border digital services and small parcel e-commerce deliveries is also a challenge.

Changes afoot

Some Asian countries have started to introduce digital services taxes—withholding taxes on payments for cross-border digital services or user-based turnover taxes on digital activities. These, however, may become redundant if a new global system for profit taxation is adopted.

As of August 2021, the United States and most major Asian economies were among the 134 members of the Inclusive Framework led by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-IF), agreeing to allocate taxing rights on profits to countries where consumers and users are located, reflecting the digital presence. Details are still under discussion, but under the agreed global reforms, a portion of profits from multinationals with global sales above EUR20 billion (roughly the 100 largest global companies) will be allocated across countries in proportion to local sales and taxed under local laws.

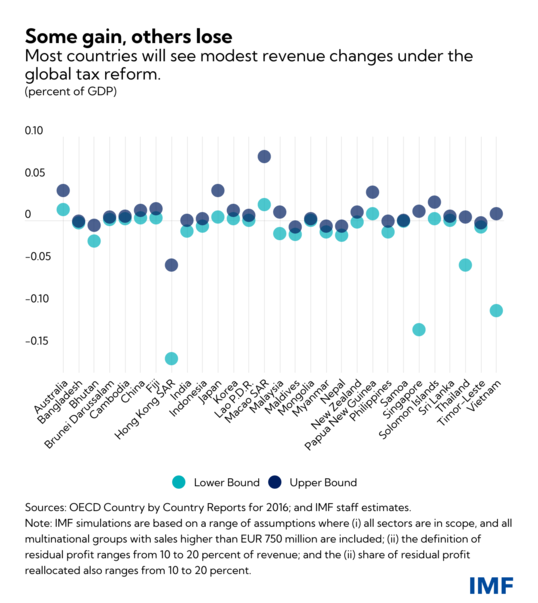

In a new IMF staff paper, we survey the digital landscape in Asia and the effect of proposals, such as that from the OECD-IF, on corporate tax revenue across Asian countries. We also outline the pros and cons of digital services taxes and estimate their revenue potential. Finally, we calculate the potential additional revenue gains from collecting value-added tax on digital services and cross-border e‑commerce sales of goods.

Investment hubs such as Singapore and Hong Kong SAR could lose up to 0.15 percent of GDP in corporate tax revenue because the profits currently declared in these countries by multinationals exceed the local share of total sales. Whereas high-income countries with large domestic markets—Australia, China, Japan, Korea—would gain revenue, developing countries such as Vietnam could lose revenue.

The agreed changes could spur more comprehensive reforms applied to all companies and to a larger share of profits. That would cause a much larger reallocation of tax revenue across countries, with the largest losses expected for investment hubs in Asia and expected gains for several developing economies.

Digital services taxes—although easier to implement—don’t raise much revenue and have other drawbacks. A digital services tax similar to India’s Equalization Levy would have yielded only 0.02 percent of GDP in 2019 for Bangladesh, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. But digital services taxes can distort business decisions and still be vulnerable to tax avoidance. They can also complicate trade relations, because they are usually applied only to large firms headquartered abroad.

Value-added taxes and digitalization

More than half of all services trade in Asia is digitally delivered, making it hard to collect value-added taxes when these services cross borders. Cross-border e-commerce sales of goods have also been exempt from value-added taxes when shipped internationally in small parcels.

Resolving these challenges pays off. Requiring nonresident suppliers of digital services and e‑commerce marketplaces to register with local tax authorities and remit value-added taxes on their sales could raise revenue between 0.04 and 0.11 percent of GDP in some countries in Asia, translating to an additional $166 million in Bangladesh, $4.8 billion in India, $1.1 billion in Indonesia, $365 million in the Philippines, and $264 million in Vietnam.

The road ahead

As Asian consumers and businesses increase their online activity in the coming years, tech giants will expand further into Asian countries, making taxation in a digitalizing economy even more important. Countries in Asia, in particular, can invest in ways to harness digitalization for tax administration helping to reduce tax evasion, boost revenue mobilization, and make tax collection more efficient. With countries further shaping the agreement in the OECD-led IF, the fundamental reforms that lie ahead may make the international tax system more robust for the digital age.

*****

Era Dabla-Norris is a division chief in the IMF’s Asia Pacific Department and mission chief for Vietnam.

Ruud De Mooij is an advisor in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department.

Andrew Hodge is an economist in the IMF’s Western Hemisphere Department.

Dinar Prihardini is an economist in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department.

Credit: The Post How to Tax in Asia’s Digital Age first appeared in the IMF Blog on 14th September 2021